In a world increasingly focused on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, manuscript scholars often face the question: why invest time and resources in studying medieval prayer books? This question is one many in the field encounter throughout their careers. At first glance, studying centuries-old, dusty manuscripts may seem difficult to justify, especially when urgent global challenges such as climate change, political instability, and a shifting media landscape demand immediate attention. Medieval manuscripts might appear outdated and irrelevant to contemporary concerns. However, a closer look reveals their profound significance. The prayer books of the Buxtehude convent, for example, show how medieval manuscripts can offer valuable insights that enhance our understanding of the present.

Technological Advances of Their Era: Roman Concrete, Medieval Prayer Books, and Modern Smart Phones

Since Apple introduced the iPhone in 2007, smartphones—mobile devices with advanced computing and connectivity—have taken over the world. They are now the dominant means of accessing the internet and and serve as a primary gateway to information, entertainment, and media (Harkin & Kuss, 2021). By 2023, 6.7 billion people worldwide were using a smartphone, with an estimated global penetration rate of 69% (Statista, 2025). Life without smartphones is becoming increasingly difficult to imagine. These devices command a significant share of daily attention, with people checking their phones an average of 58 times per day (Duarte, 2025) and spending 4 hours and 37 minutes on them—amounting to nearly one full day per week or six days per month. For many, the absence of a smartphone triggers a sense of discomfort known as nomophobia (Han, Kim & Kim, 2017). Given these facts, it is more than justified to call the present era the age of the smartphone.

Over the past decades, smartphones have become lighter, smaller, and yet more capable, integrating the latest technological advancements. When compared to cutting-edge innovations like the latest smartphone, it may seem counterintuitive to think of prayer books—or really anything from the Middle Ages—as technologies. Unlike modern devices, prayer books contain no advanced microprocessors, nor do they offer artificial intelligence support—hallmarks of humanity’s ongoing technological progress. However, this perception changes when we reconsider what we mean by technology. The term dates back to the early 17th century, originally referring to the “terminology of a particular art or subject.” From the 19th century onward, it came to denote the “application of such knowledge for practical purposes,” and by the late 19th century, it also referred to “the product of such application” (Simpson & Weiner, 1989). This broader perspective allows us to view pre-modern inventions as forms of technology as well.

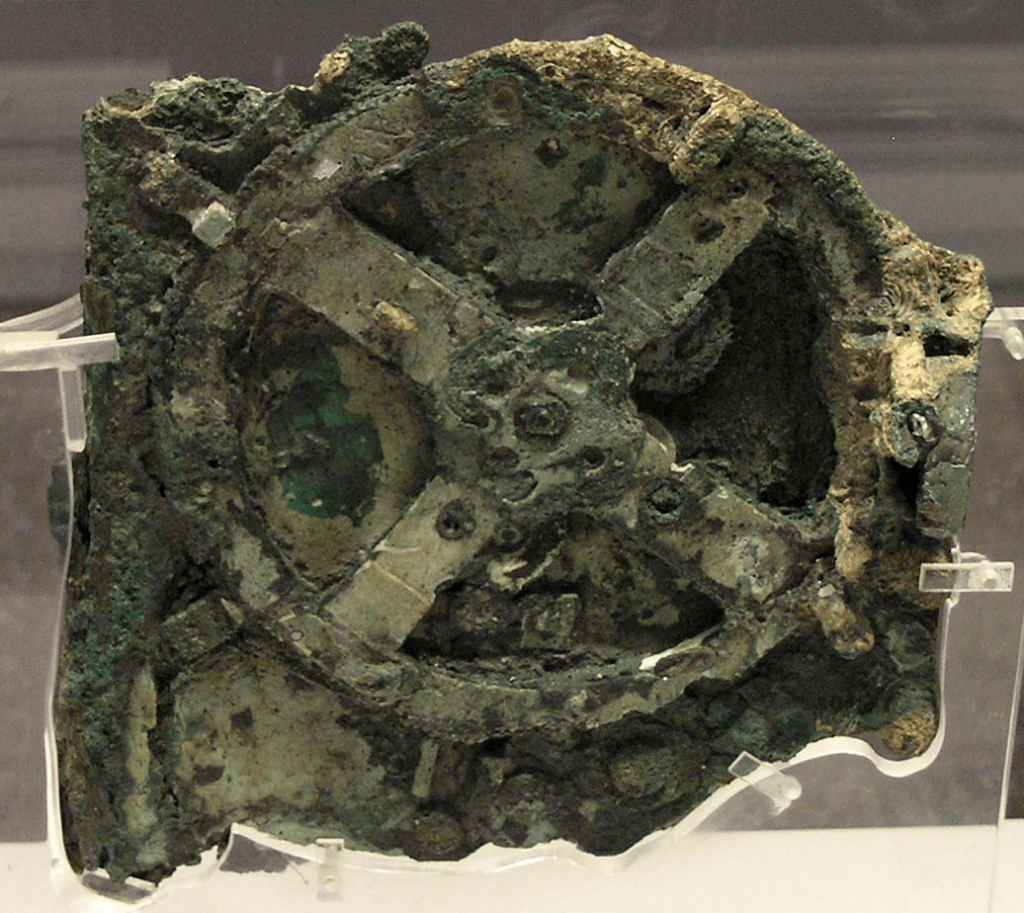

Ancient civilizations, for example, developed technologies that radically transformed society, such as the wheel, invented around 4000 BCE (Gasser, 2003; Anthony, 2007). It revolutionized trade and warfare and, alongside other technological advances, helped usher in the Bronze Age (c. 3300–1200 BCE). As one of the six classical simple machines used to multiply force, the wheel is so fundamental that it’s difficult for us today to imagine a world without it. However, some advanced Native American societies—the Aztecs, Incas, and Maya—never invented the wheel, reminding us that technological innovations are neither universally necessary nor inevitable. Other ancient innovations challenge our imagination, such as the Roman aqueducts. Between 312 BCE and 226 CE, engineers constructed eleven waterways in the city of Rome alone, spanning just over 800 km—less than 47 km of which ran above ground. Supplying an estimated population of one million people, these aqueducts delivered between 520,000 and 1,000,000 cubic meters of water. In some cases, ancient technologies were not only remarkably sophisticated but even more advanced than their modern counterparts. Roman concrete, for instance, outperforms modern concrete in strength, versatility, and durability. Its secret lies in the use of pozzolanic ash, which not only prevented cracks from spreading but also enabled self-repair (Chandler, 2023). And yes, in some cases, we simply do not know the exact purpose of certain technologies. The Antikythera mechanism, for example—a mysterious Hellenistic device from the 2nd century BCE—is believed to be the first analog computer, yet its full function remains a subject of ongoing debate (Freeth et al., 2006).

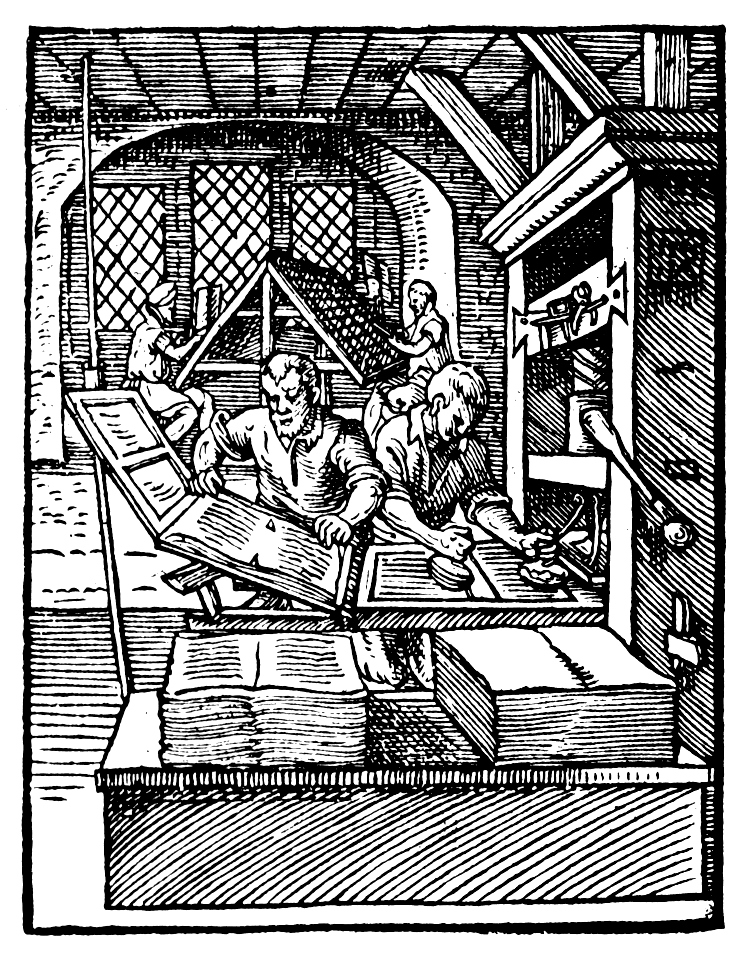

Contrary to popular belief, the Middle Ages were not a period of stagnation but an era of remarkable and lasting technological innovation (Falk, 2020; Gies & Gies, 1994). Far from a “dark age” that set humanity back, it was a time of progress, laying the foundation for many advancements that still shape modern life. One striking example is the mechanical clock. While timekeeping devices existed in Antiquity, it was not until the 13th century that mechanical clocks could measure time with precision, fundamentally altering daily life by making time an essential organizing factor. Another transformative invention was gunpowder. Developed in China between the 9th and 11th centuries, it spread across Eurasia by the 13th century, eventually rendering knights and castles obsolete (Andrade, 2022). Perhaps the most influential innovation of the late Middle Ages was Johannes Gutenberg’s refinement of movable type and the printing press. His invention revolutionized book production, democratized knowledge, and reshaped the media landscape, paving the way for the modern information age.

But even when we consider the Middle Ages as a time of technological progress, it can still be difficult to view prayer books as a significant technological advancement. At first glance, they seem detached from traditional fields of science—there’s no physics, no optics, no mechanics, no chemistry, no mathematics, and no engineering involved. Yet, a compelling argument has recently been put forward by Sherry C. M. Lindquist in her 2024 publication The Book of Hours and the Body. Drawing from post-humanist discussions on humanity’s potential to transcend its inherent limitations, Lindquist argues that prayer books—especially through their elaborate imagery—served as a “technology” that functioned as a “mechanism through which a reader might forge another (posthuman) self” (p. 90). Scholars such as Beth Rothstein and Beth Williamson have similarly characterized Books of Hours as “devotional technologies” (p. 99).

Devotional Technologies: Prayer Books as Gateways to Heaven

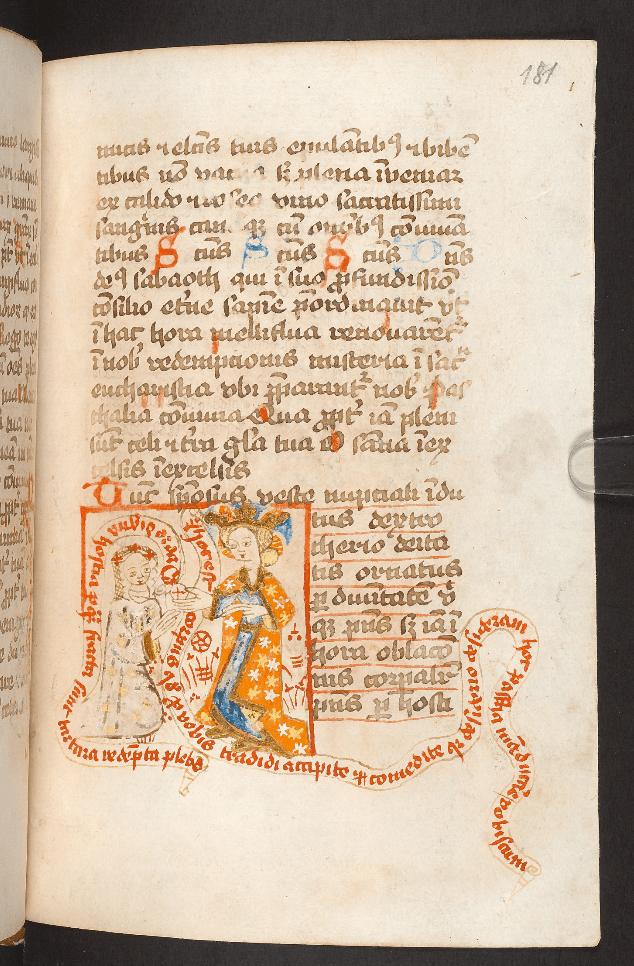

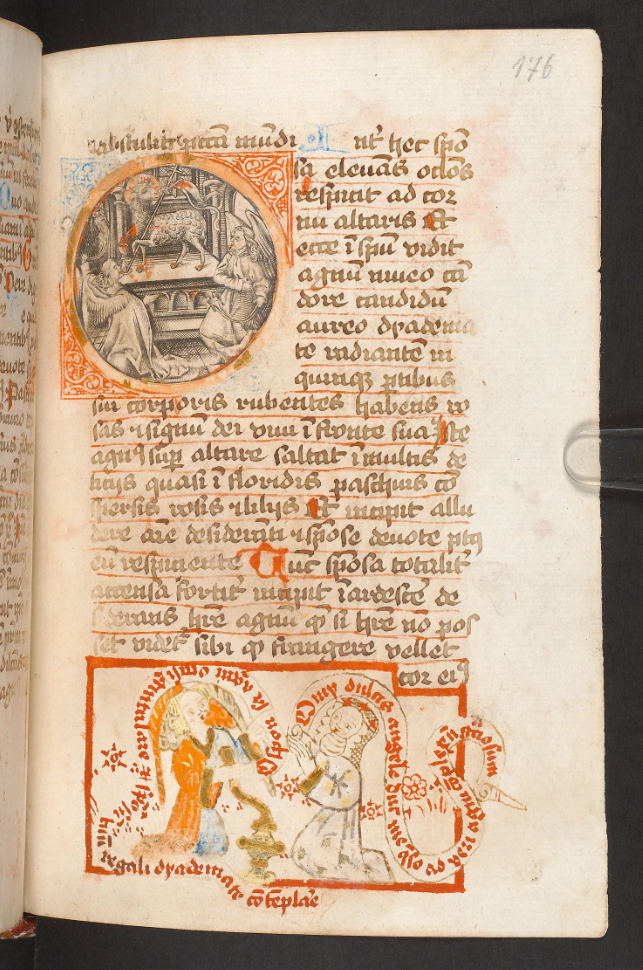

The Buxtehude prayer books represent a technological response to a profound question: how can one cultivate a relationship with an omnipresent yet elusive presence—the Divine? Through their intricate designs, structured textual arrangements, and detailed illuminations, these prayer books functioned as powerful devotional tools, designed to foster a deeper spiritual connection. At the intersection of religious devotion and technological innovation, they granted their owners privileged access to Christ and reinforced the promise of salvation. A striking example of this can be found in Cecilia Hüge’s Easter prayer book, now housed in the Landesbibliothek Württemberg (Cod. brev. 22). For the First Mass on Easter Sunday, when the nuns received Holy Communion, the manuscript provides an extended dialogue between Christ and his bride. This dialogue weaves together texts from the official liturgy with private devotional passages, enabling the nuns to cultivate a personal and intimate relationship with Christ. The intensity of this spiritual connection is further reinforced by the accompanying miniature on 181r. It depicts a nun in a white habit kneeling before the resurrected Christ, both figures nearly touching but separated by a small gap—symbolizing the divide between the earthly and heavenly realms. At the center of the composition is the Eucharistic host, visually emphasizing its role as the essential medium that bridges this divide. Throughout Cecilia’s prayer book, Eucharistic devotion permeates both text and image, positioning the manuscript as a highly specialized technology designed to facilitate communication with the divine and make salvation tangible through the Eucharist.

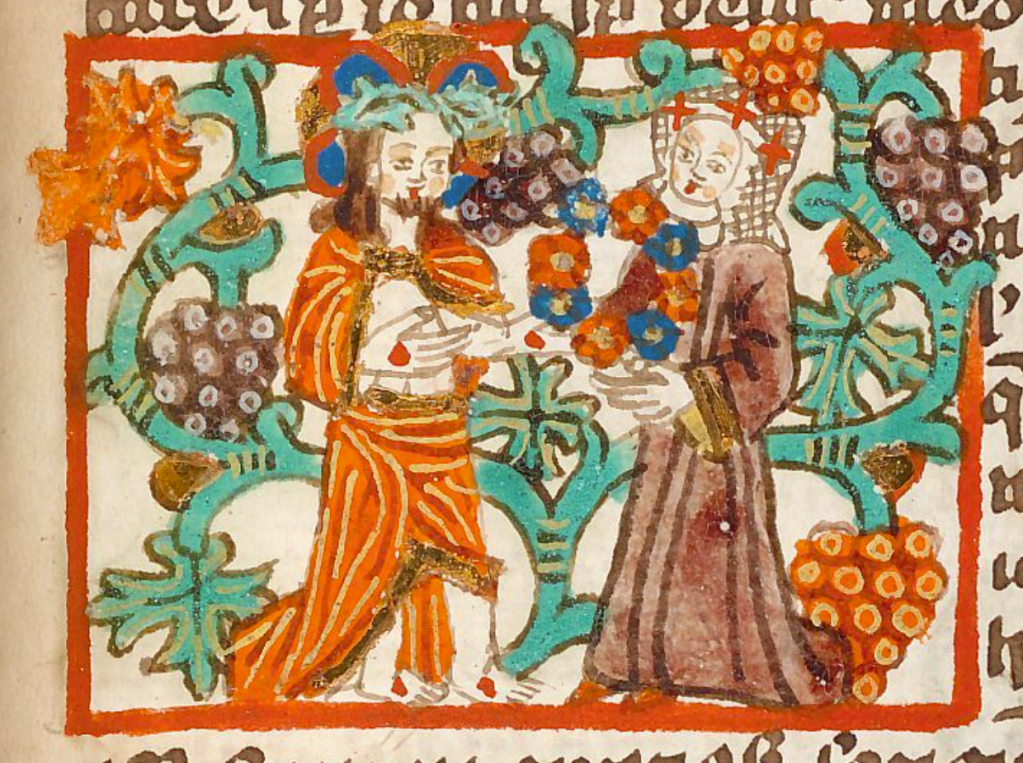

Further along in the prayer book, the visual argument of the aforementioned miniature is not only repeated but reinforced. The miniature on 360r depicts the Resurrected Christ on the left, clothed in red and gold garments, with visible stigmata, approaching a nun in a dark habit on the right. Their gazes are locked, their bodies turned toward one another, the miniature clearly captures an intimate moment between the two figures. Christ offers the nun a floral crown, which the nun gratefully accepts. In the case of this miniature, the separation between the heavenly and the earthly realms is intentionally blurred: Although there appears to be no physical contact between the two figures, they subtly enter each other’s space. Moreover, the exchange of a gift serves as a tangible reminder of the heavenly realm, passed down into the earthly sphere. Encircling the scene is a vibrant grapevine, symbolizing the Eucharist as the unifying bond between Christ and his bride. This core message is conveyed explicitly through both text and image in Cecilia’s prayer book, further emphasizing the role of prayer books as devotional technologies that shape and communicate the convent’s devotional profile and core beliefs.

Medieval Prayer Books and Modern Smartphones: Technologies Designed to Access Intangible Realms

Despite being separated by at least 500 years, prayer books and smartphones can be seen as technological responses to the same fundamental challenge: accessing an otherwise invisible and intangible realm—the heavenly sphere in the case of prayer books, and the digital world, particularly the internet, in the case of smartphones. At first glance, this comparison may seem far-fetched, but upon closer examination, striking similarities emerge between these two technologies, which I will explore in the following.

The internet, born in the United States in the 1970s, has grown into an invisible force that connects billions of people worldwide. By 2020, more than half the global population—around 4.5 billion people—were online, and that number keeps climbing. Yet, despite its omnipresence, the internet remains intangible; you can’t step inside it, touch it, or physically enter cyberspace. At the risk of sounding heretical, the heavenly realm operates in much the same way—at least for everyone except Christ and the Virgin Mary, who, according to Christian belief, ascended bodily into heaven. Both the digital and the divine are ever-present yet beyond direct human reach. And to bridge the gap between these realms and the earthly world, we rely on technology. For modern users, smartphones serve as portals to the digital sphere, allowing seamless access to information, communication, and entertainment. For medieval nuns, prayer books played a similar role—not as mere collections of texts and images, but as devotional technologies designed to transport their readers into the divine presence. In this way, both prayer books and smartphones turn their users into cross-border commuters, moving between the physical and the immaterial with the help of the right tools.

Another striking similarity between smartphones and prayer books is their capacity for customization. When someone first acquires a smartphone, it’s essentially a blank slate—ready to be tailored to individual needs. Users personalize their home screens, and create shortcuts to frequently used apps. These apps function as filters, shaping how people access and interact with the digital realm. The Buxtehude prayer books worked in much the same way. Just as smartphone users curate their digital experiences, the nuns actively shaped their engagement with the divine, selecting specific devotional “channels” that mediated their relationship with God. Cecilia, for example, integrated parts from an hitherto unidentified woodcut to illuminate the text in her Easter prayer book.

But the flexibility of prayer books went even further—they weren’t just customizable; they were adaptable over time (Rudy, 2016). Today, we often think of books as static objects, fixed in form and content. This perception stems from our modern understanding of authorship—where a book is seen as the definitive, original work of a single genius. But in the past, books were anything but static. They were fluid, evolving objects that could be reshaped to meet their owners’ needs. For medieval nuns, a prayer book was not a finished product but a work in progress, capable of changing alongside their spiritual lives. If a nun’s devotional focus shifted, so too could her book. Some changes were dramatic—entire quires could be inserted, removed, or rearranged, requiring the book to be unbound and rebound. Other modifications were more subtle: texts could be erased, sometimes scraped away with a knife, to make room for new prayers or reflections. These weren’t mere edits; they were conscious acts of devotion, personalizing and refining the way nuns connected with the Divine. A fascinating example of this adaptability can be seen in the recently discovered Buxtehude prayer book housed in the Dombibliothek Hildesheim. Many of its quires were added at a later stage, though the precise circumstances of these alterations remain a mystery, inviting further investigation.

Each modification in the prayer books reshaped their meaning, making earlier versions difficult—sometimes impossible—to reconstruct. While modern technology can sometimes recover hidden texts, like through the analysis of palimpsests, much is still lost. This dilemma isn’t limited to medieval manuscripts; it mirrors recent developments in digital communication. Since May 2023, WhatsApp has allowed users to edit sent messages, while from September 2024, paid users on X (formerly Twitter) can modify a post within a 60-minute window. These features highlight a critical issue: the ability to alter information after publication. Just as medieval scribes reshaped prayer books, today’s digital tools enable users to rewrite history in real time—raising important questions about the permanence of information and the wider implications of revision in both spiritual and digital realms.

At the same time, this comparison raises broader questions about the longevity of both premodern and modern technologies. As the gap between smartphone generations shrinks, consumers face increasing pressure to keep up with the latest advancements. In 2015 alone, 26 million smartphones were sold in Germany, bringing the total number of users to 49 million. Yet, when these devices break, most people don’t attempt repairs—only 11% have ever tried to fix a broken electronic device. Instead, they opt for replacement, contributing to an average of 21.7 kilograms of electronic waste per person each year—second only to the United States, which generates 22.1 kilograms (Greenpeace, 2016). This cycle of rapid consumption places a significant strain on the environment.

By contrast, prayer books were designed for endurance. Rather than being discarded, they were passed down through generations (Rudy, 20216), evolving alongside their users. Given the high cost of book production, acquiring a new prayer book was often impractical, so people became skilled at repurposing existing ones to suit their changing needs. Pages were added, texts were modified, and bindings were replaced—ensuring that these devotional tools remained relevant over time. In an age where planned obsolescence drives consumer habits, the adaptability of premodern books offers a striking counterpoint: a technology built not for disposal, but for longevity and renewal.

Take Home Message

At first glance, prayer books and smartphones couldn’t be more different. Yet, both function as customizable, interactive technologies that mediate access to otherwise intangible realms. The key difference? Their lifespan. While smartphones are rapidly discarded and replaced, medieval prayer books were preserved, adapted, and repurposed for generations. This contrast prompts a crucial question: how do we engage with technology today? Do we see our digital tools as fleeting and disposable, or do we consider their long-term impact? The Buxtehude prayer books remind us that technology isn’t just about innovation—it’s about sustainability, adaptability, and the ways in which we shape, and are shaped by, the media we use. Looking back at medieval prayer books might just offer us fresh insight into how we approach technology in our own time.