Female empowerment—this is one of the central themes in the Latin and Low German Easter prayer book of Cecilia Hüge (Stuttgart, Landesbibliothek, Cod. brev. 22). Nowhere is this more evident than in its vibrant illuminations, which portray the Buxtehude nuns as powerful intercessors between the heavenly and earthly realms. These images challenge conventional hierarchies, suggesting that the nuns saw no need for a male mediator. On the contrary, the illuminations assert that divine intercession was their responsibility. This blog post explores the theological foundations behind these images and what they reveal about the devotional profile of Neukloster Buxtehude.

Let’s begin our investigation by examining the colorful miniature above. The miniature is part of Cecilia’s Easter prayer book. At the center of the illumination stands Christ, represented as the Agnus Dei, the Lamb of God. This title refers to Christ’s redemptive role. It refers to the Gospel of John: “Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world„” (Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi), as proclaimed in John 1:29, and reaffirmed in John 1:36. The Book of Revelation further reinforces this imagery, containing over twenty-nine references to a lion-like lamb, described as “slain but standing” (Revelation 5:6).

In miniature above, the Agnus Dei occupies the central position of the image. It is large in size, and its white fur, accented with blue highlights, further draws the viewer’s attention. The lamb is depicted with a halo and holds the resurrection banner. Its head turns toward the fluttering banner at the center of the image, emphasizing its symbolic importance. The halo and banner are rendered in vibrant colors with an impressive use of gold. In direct reference to Revelation 5:1–13, the Agnus Dei is shown bleeding from the heart, symbolizing Christ’s sacrifice for the redemption of humankind (cf. John 1:29, 1:36). The blood flows into a golden chalice placed before the lamb, reinforcing Eucharistic symbolism. Additionally, the stigmata are subtly indicated as red dots, underscoring Christ’s Passion and its salvific significance.

This iconography appears throughout Cecilia’s prayer book, including on 141v. Here, the Agnus Dei is depicted without any surrounding figures. A red frame encloses the Lamb of God, with only the resurrection banner breaking through its borders. Some of the gold in the upper section of the standard has worn away, revealing the underlying priming coat and providing valuable insights into the miniature’s production process. From the Medingen prayer books, we know that the nuns were not only responsible for writing the texts but also for creating the illuminations—a practice that was likely followed in the Buxtehude prayer books as well.

Stuttgart, Landesbibliothek, Cod. brev. 22, 141v.

Back to the image from the beginning, the Agnus Dei is surrounded by two angels in the upper part of the image and two Buxtehude nuns in the lower part, representing both the heavenly and earthly realms. The angels in the upper corners of the image, adorned in colorful robes with golden hems, gesture towards the lamb at the center of the miniature. Meanwhile, the nuns in the lower corners attired in monastic habits kneel, their gazes fixed upon the lamb before them. Both nuns don the nuns’ crown, an indication of their status as brides of Christ, yet they appear in different habits: the nun to the left is clothed in a bright white habit, while the other on the right wears a significantly darker outfit. Further research is warranted to ascertain whether this depiction correlates with the convent’s transition from the Benedictine to the Cistercian order within the context of monastic reform.

The Agnus Dei in the Medingen Prayer Books

This image formula is not a novel invention by the Buxtehude nuns. Rather, it appears to be a well-established motif within the female convents of North Germany. One example for comparison is the manuscripts from the Cistercian convent of Medingen. Currently, the Medingen corpus comprises 65 Latin and/or Low German manuscripts produced by the nuns themselves between the early 15th and the mid-16th centuries. Among the oldest surviving prayer books from Medingen is a manuscript now housed in the Landesbibliothek Hannover (Ms I, 75). This manuscript, which has largely remained unexplored to date, likely predates the Copenhagen Easter prayer (Royal Library, Ms GKS 3452-8°), completed by the Medingen nun and subsequent prioress Cecilia de Monte in 1408. On page 247, an 11-line historiated initial accompanies a Latin Salutation to Christ. Within the inner field of the S-shaped gold initial is a depiction that is remarkably similar to the Buxtehude miniature: a group of five nuns—note particularly the nun on the right, whose head protrudes in an awkward manner akin to a group photograph in which each individual desires to be seen—venerating the Lamb of God to the right.

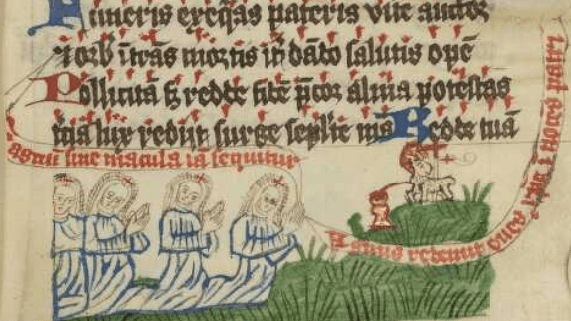

Although certain elements from the Buxtehude version—predominantly the Golden chalice—are absent, there exist significant similarities between the two illuminations: both emphasize the direct connection of the nuns to the Divine. Notably absent are male priests or confessors who might otherwise act as intermediaries between the two parties. The message is evident: the nuns do not require a male presence to establish their connection with God. As brides of Christ, as suggested by the visual argument of the image formula, they possess a unique access to Christ and, consequently, to salvation. In the initial of the Hannover prayer book, this notion is further reinforced by the gazes depicted: in this version of the image, the lamb, positioned at the same level as the nuns, directly engages with the women, who in turn gaze directly at the viewer.

As other examples from the Medingen corpus suggest, this image formula appears to have been an integral component of the convent’s devotional profile throughout the 15th century. One illustrative example can be found in a Latin and Low German Easter prayer book currently housed in the Dombibliothek Hildesheim (Ms. J 29). This small yet significant volume was produced within the context of the North-German monastic reform and was completed by the Medingen nun Winheid von Winsen, possibly in 1478. In contrast to the Buxtehude version of the image, the Medingen illumination distinctly separates the nuns on the left from the lamb on the right, which is depicted upon a small hill, alluding to the separation between earthly and heavenly realms. A comparison of both Medingen miniatures may indicate a shift in the convent’s devotional profile during the 15th century, with an increased focus on the Eucharist.

What Makes the Buxtehude Version of the Agnus Dei Special

What stands out in the Buxtehude image is the closeness of the nuns to the Lamb of God, a connection also seen in other illustrations from the Buxtehude convent. In the Buxtehude image the separation between the heavenly and the earthly realms is not as clear as in the Hildesheim miniature. For example, spaces of the nun to the left and the lamb overlap, hence leading to an intertwining of the heavenly and the earthly realms. At this juncture, it remains unclear whether the chalice’s placement in the Buxtehude miniature alludes to similar shifts within the Buxtehude devotional profile: in the Buxtehude version, the chalice is located directly in front of the nun in white habits to the left. The habit of the nun touches the chalice, and the gold of the cup appears to blend with the gold from the embellishment of the habit. In contrast, the nun in the darker habit does not make contact with the chalice and is positioned further away from the lamb. Interpreting this finding within the context of the convent’s history, it may imply a reinforcement of Eucharistic devotion amid the monastic reform, which the Buxtehude nuns sought for a more intimate connection to Christ and enhanced access to salvation.

Other Examples of ‘Closeness’

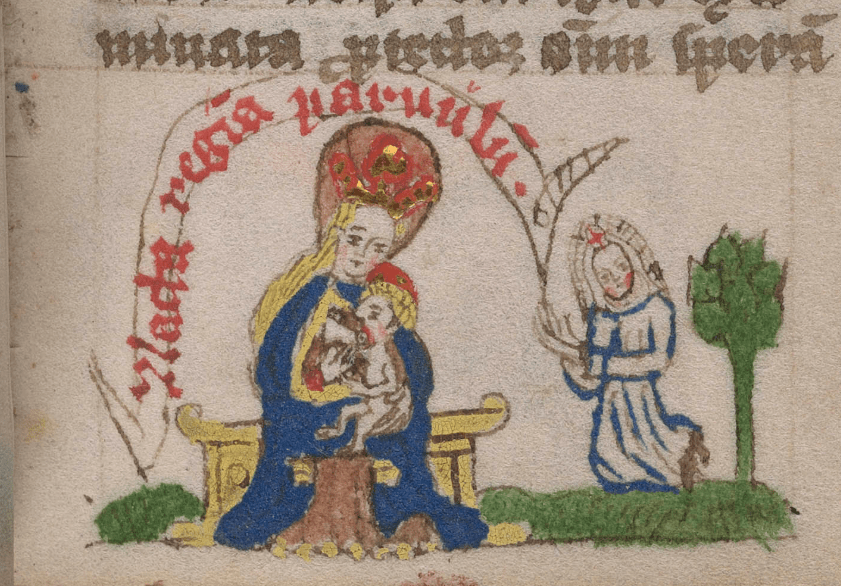

The left image from the Buxtehude prayer book at the University of Cincinnati (Ms 002, 42v) shows Mary, crowned as the Queen of Heaven, sitting on a throne. According to the iconography of Madonna lactans, she is breastfeeding the infant Jesus, surrounded by two angels, with a nun in a dark habit kneeling in front of her. This nun gazes at Mary, who returns the intimacy, and stretches out her hands as if to hold Jesus. This portrays the Buxtehude nun as one who can connect the heavenly and earthly realms. In contrast, the image on the right, taken from a Medingen psalter in the Chapin library (Ms 008, 34r), shows a nun farther away from the Virgin Mary. She is connected to the Divine but remains grounded on earth, as indicated by the tree behind her.

Take Home Message

A close look at the visual language of the Buxtehude manuscripts reveals a striking theme: the nuns’ intimate and direct connection to the Divine, unmediated by male clergy. Through carefully crafted illuminations, they asserted their role as spiritual mediators, subtly challenging traditional hierarchies and claiming a space of agency within their devotional practices. The vibrant, layered imagery invites us to reconsider how these women saw themselves—not as passive recipients of grace, but as active participants in shaping their spiritual lives. By intertwining heaven and earth in their art, the Buxtehude nuns offer a powerful reminder of how visual culture can articulate complex theological ideas and empower those who create it.