The starting point for this post is a small, striking image in a late medieval Christmas prayer book now preserved in the Archives and Rare Books Library at the University of Cincinnati (Ms 2). The manuscript, written in Latin and Low German around 1500, can be linked on paleographical and stylistic grounds to the Benedictine convent of Neukloster in Buxtehude. In it, liturgical texts for the Christmas season are interwoven with prayers and illuminations that invite an affective, sensory engagement with the feast.

One miniature on fol. 40v crystallises this programme of devotion. A nun in dark habit and white veil, marked as a sponsa Christi by her nun’s crown, stands at the foot of a cradle. The long side of the crib, shown in profile, is painted with bright red, blue, and green floral motifs. Inside lies the Christ Child, his lower body wrapped in an orange blanket, his bare chest exposed, his head resting on a tasseled cushion. He turns toward the nun, his hands raised in an almost conversational gesture. The nun, in turn, places both hands on the rails of the cradle, as if setting it in motion, her gaze fixed steadily on the Child. Three angels with vividly coloured wings stand nearby, unfurling scrolls inscribed with hymn incipits.

The scene is deceptively simple. Yet it condenses central themes of late medieval female devotion. The reciprocal exchange of gazes between nun and Child visualises an intimate, affective relationship; the action of rocking locates that relationship in a bodily gesture of care. The angels’ scrolls render audible what the page itself cannot sound, summoning the convent’s liturgical music to mind. In this way, text, image, movement, and remembered sound converge on a single, small act: rocking the Christ Child at Christmas.

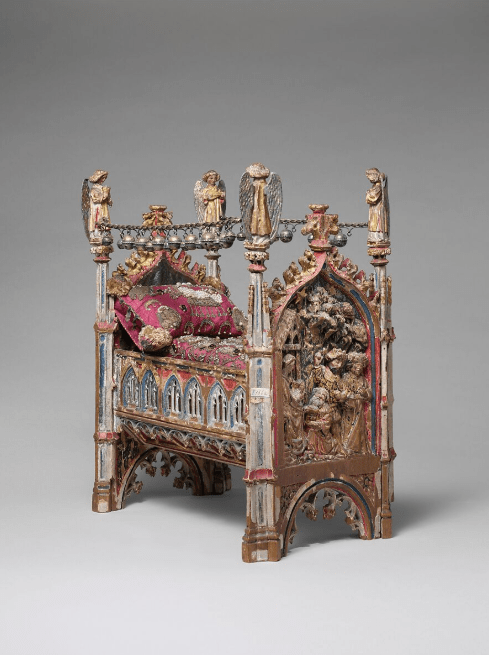

The miniature gains further depth when read against the material culture of devotional cradles. A well-known example is the fifteenth-century Crib of the Infant Jesus from the Great Beguinage of Leuven, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Carved in the form of a miniature Gothic structure and enriched with polychromy, precious metals, enamels, and embroidered textiles, it once held a Christ Child figure and was designed to be rocked; attached bells produced a soft chime when the cradle moved. Sight, touch, and sound thus formed a carefully orchestrated ensemble, inviting the devotee to re-enact Mary’s care for the newborn Christ through a multisensory ritual.

Caroline Walker Bynum has highlighted the “seductive materiality” of such cradles, arguing that their rich surfaces and moving parts were not mere ornament, but means by which women religious engaged the Incarnation as a tangible, bodily reality. The Cincinnati illumination transposes this material culture into the medium of the book. The painted cradle echoes the visual logic of its wooden counterparts, but is integrated into the manuscript’s page layout: its floral decoration resonates with the penwork initials and border motifs, visually binding the object to the surrounding text. Here, the crib is, quite literally, “built” out of ink and pigment; the Christ Child is sustained by the nuns’ reading as much as by an imagined textile.

The scene also invites interpretation through theoretical work on medieval images and devotion. Hans Belting has argued that pre-Reformation sacred images were experienced not primarily as “art,” but as sites of presence—media through which the holy became tangibly accessible to the faithful. In the Cincinnati miniature, this logic of presence is doubled: the Christ Child is present for the nun within the fictive space of the image, while the image itself becomes present to the nun (and, later, to us) as an object that structures and stimulates prayer.

Jeffrey Hamburger’s concept of the “performative image” is especially helpful here. In his work on art and female spirituality, he has shown how images produced in women’s communities often functioned as scripts or models for devotion—images that do not simply depict prayer, but enact and elicit it. The nun rocking the cradle in Ms 2 can be read in precisely this way. She demonstrates the ideal devotional posture for the manuscript’s reader: absorbed attention, bodily engagement, and affective proximity to Christ. The image thus mediates between visionary experience and everyday practice, between interior prayer and outward, almost domestic gesture.

This performative quality is closely aligned with the spirituality of the Devotio moderna, which shaped reform movements in Northern Germany around 1500 and encouraged believers to imagine biblical scenes in concrete, sensory detail. Authors such as Thomas à Kempis urged readers to place themselves “inside” the Gospel narratives, to see and feel the circumstances of Christ’s life. The Christmas prayer book in Cincinnati does exactly this: it leads the reader from the liturgical recitation of the Nativity to an imagined yet embodied intimacy in which the nun rocks, comforts, and converses with the Child.

For contemporary observers, the world of devotional cradles and illuminated orationals may seem remote. Yet the miniature in Ms 2 demonstrates how powerfully a single image can orchestrate text, gesture, and imagination to make the Christmas mystery present. At the threshold between the late Middle Ages and the Reformation, the women who used this book took seriously the idea that God became small enough to be held. In the quiet space of the manuscript’s folio, that theological claim is articulated not in abstract terms, but in the simple rhythm of a cradle gently set in motion.

Leave a comment